Oracle PL/SQL Tutorial

PL/SQL or procedural language/structured query language, is a combination of SQL with the procedural features of programming languages. We’ll provide you with a solid foundation in this PL/SQL tutorial so you can go on to the Oracle database and other advanced RDBMS concepts.

Oracle PL/SQL Basics

For developing essential applications that run on the Oracle database, PL/SQL provides more comprehensive programming capabilities. For those who are interested in databases and other cutting-edge RDBMS technology, learning PL/SQL is crucial.

Features of PL/SQL

- SQL and PL/SQL have close integration.

- It provides a wide range of comprehensive error-checking features.

- Many data types are supported for versatile data handling.

- contains a range of programming constructs, including conditionals and loops. contains a range of programming constructs, including conditionals and loops.

- It uses functions and procedures to assist structured programming.

- It facilitates object-oriented programming, which makes handling and manipulating data more sophisticated.

- It facilitates server pages and web application development.

Because of its many advantages, PL/SQL is a crucial skill for database engineers.

- It is simple to write and read in PL/SQL.

- PL/SQL programs are completely transferable between various Oracle databases.

- SQL and PL/SQL have close integration.

- PL/SQL optimizes performance by reducing network traffic.

- To ensure database integrity, it has strong security measures.

- Object-oriented programming is supported.

- Object types that can be utilized in object-oriented designs can be defined in PL/SQL.

Block-Structured Approach of PL/SQL

PL/SQL uses a technique called block-structured programming, which divides programs into logical code blocks. Every block comprises three primary components.

Declarations: These are optional and are used to define subprograms, variables, cursors, and other necessary block parts.

Executable Commands: This required portion, which is enclosed between the terms BEGIN and END, includes executable PL/SQL commands. It must have at least one line of executable code, even if that line is nothing more than a NULL command that does nothing.

Exception Handling: This optional section, which begins with the keyword EXCEPTION, addresses how to handle program errors by using defined exceptions.

Applications of PL/SQL

Many different programs use PL/SQL, including

Database Security: It incorporates strong security protocols into the database.

XML management is the process of creating and overseeing XML documents inside a database.

Connecting Databases to Web Pages: This technique combines web applications with databases.

Automation: For effective management, automate database administration chores.

PL/SQL Environment Setup

You must install the Oracle RDBMS Server on your computer to run PL/SQL programs. This will handle the execution of SQL commands. Oracle RDBMS version 11g is the most recent version.

Oracle 11g is available for trial download at this URL.

Install Oracle 11g Express Edition.

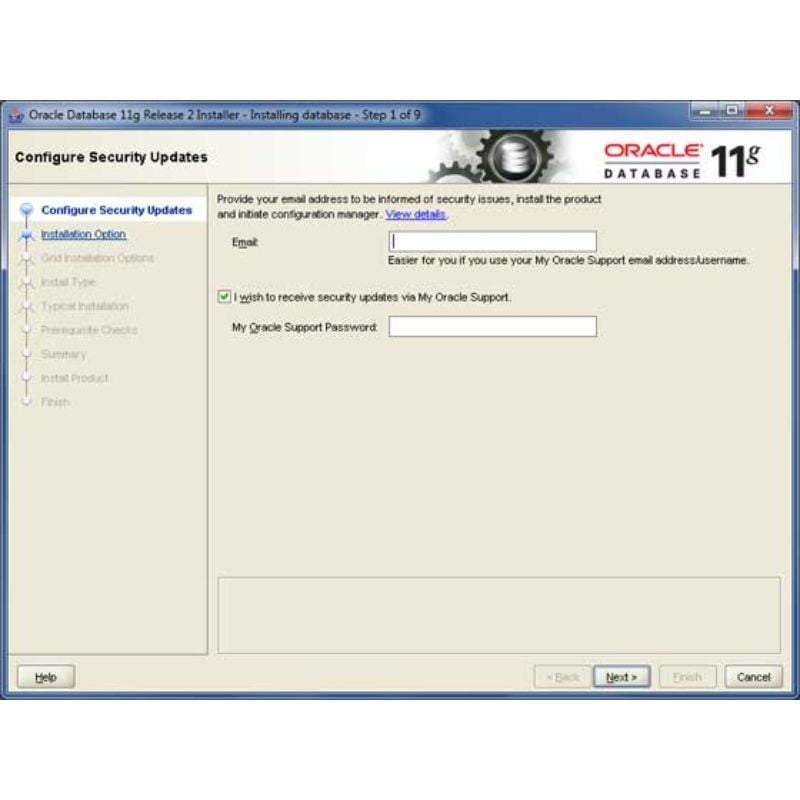

Step 1: Now let’s use the setup file to start the Oracle Database Installer. Now you can enter your email address. Press the next button.

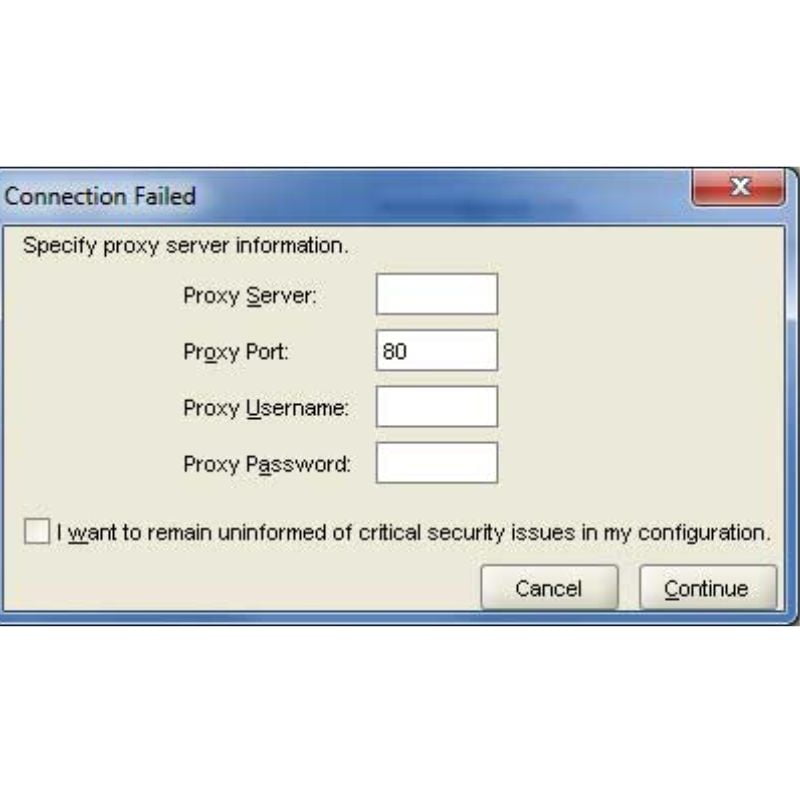

Step 2: Now click the Continue button to move forward and uncheck the checkbox.

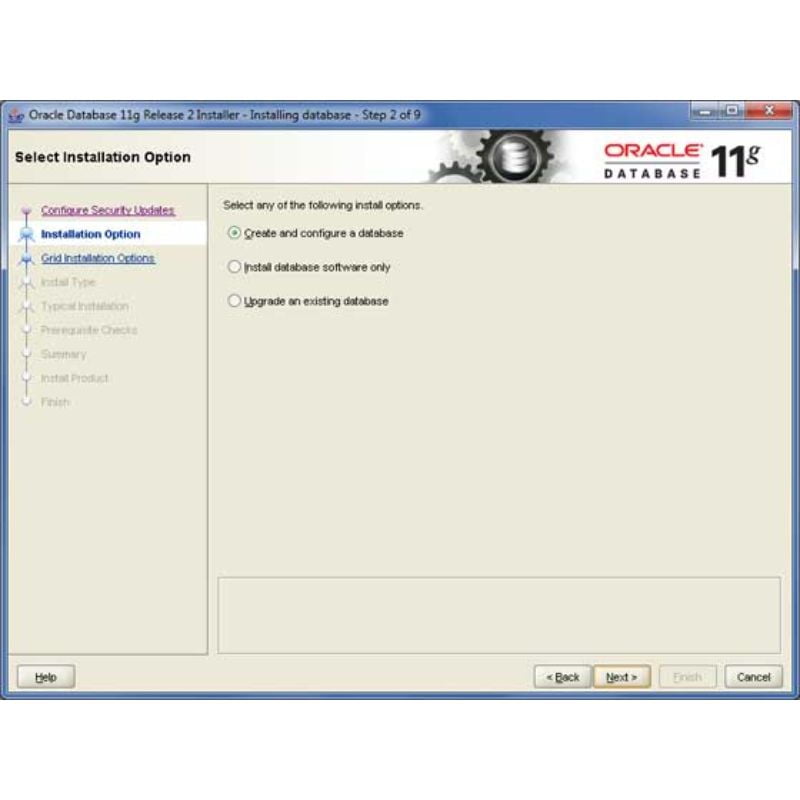

Step 3: To start, click the Next button after selecting the first option, Create and Configure Database, using the radio button.

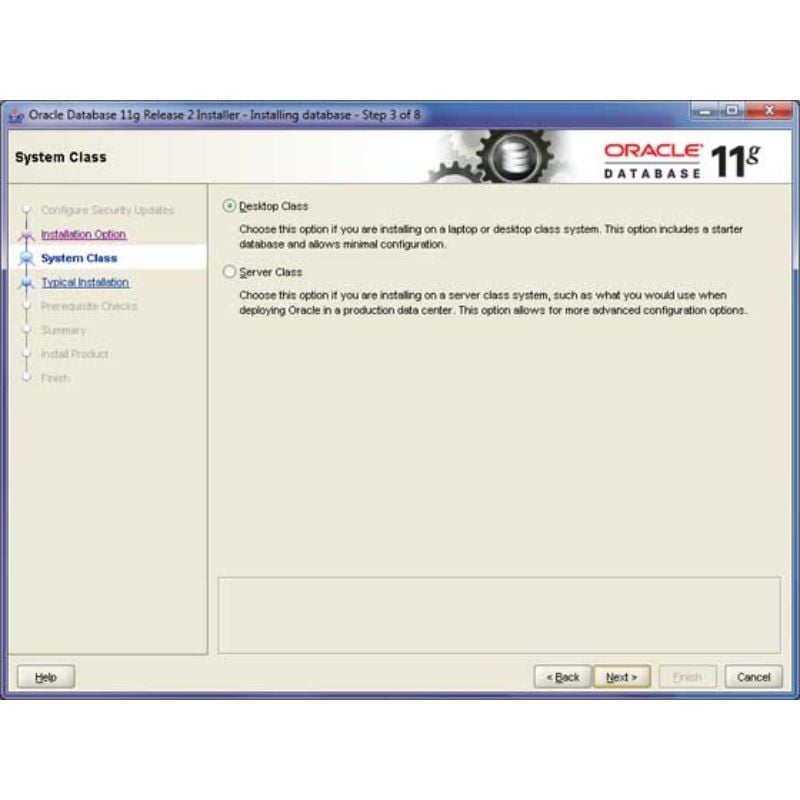

Step 4: We’ll presume that you’re installing Oracle on your PC or laptop with the primary goal of learning. To continue, pick Desktop Class and click the Next button.

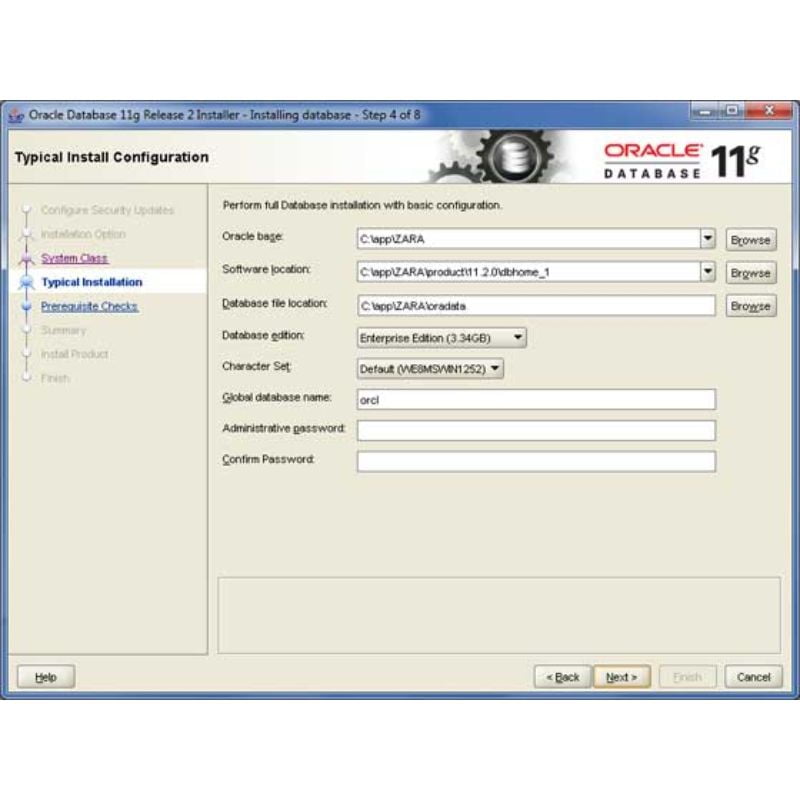

Step 5: Give the location of the Oracle Server installation. Make changes to the Oracle Base, and the other sites will adjust. The system DBA will utilize the password that you are required to supply. Once the necessary data has been entered, click the Next button to continue.

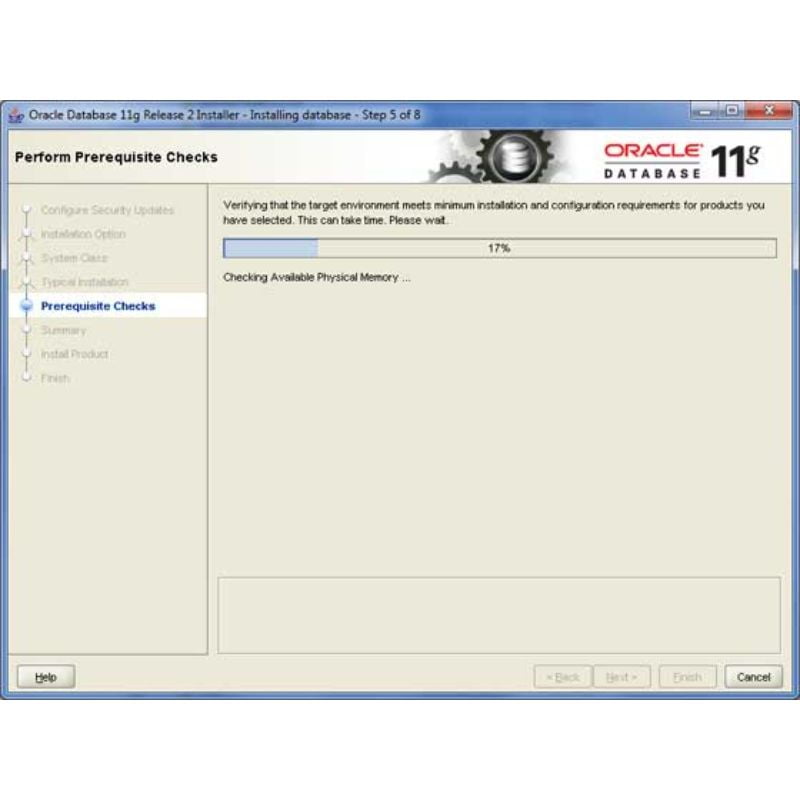

Step 6: To continue, click the Next button one more.

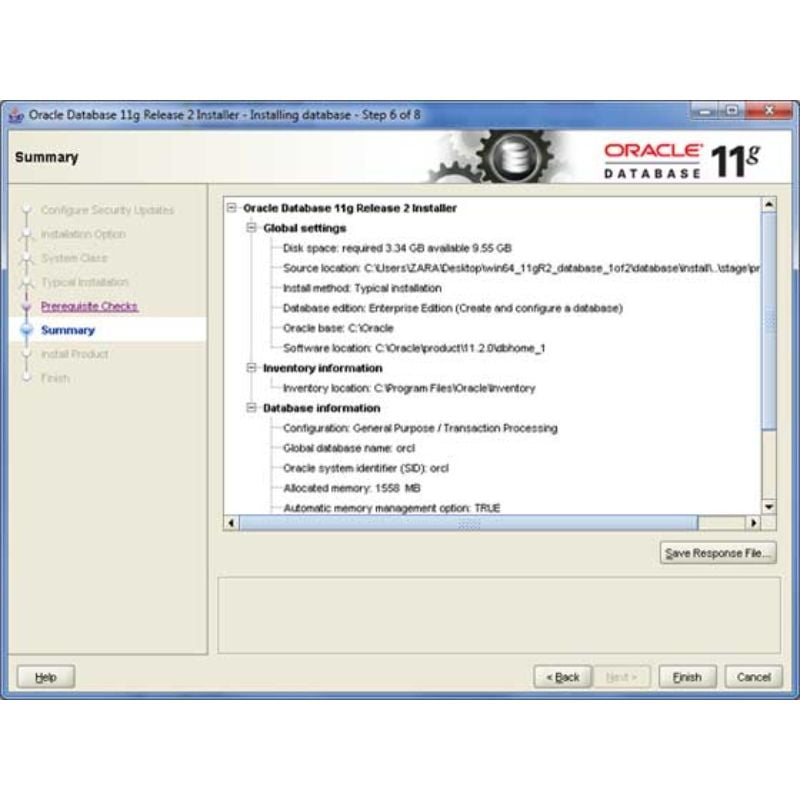

Step 7: To continue, click the Finish button, which will initiate the server installation process.

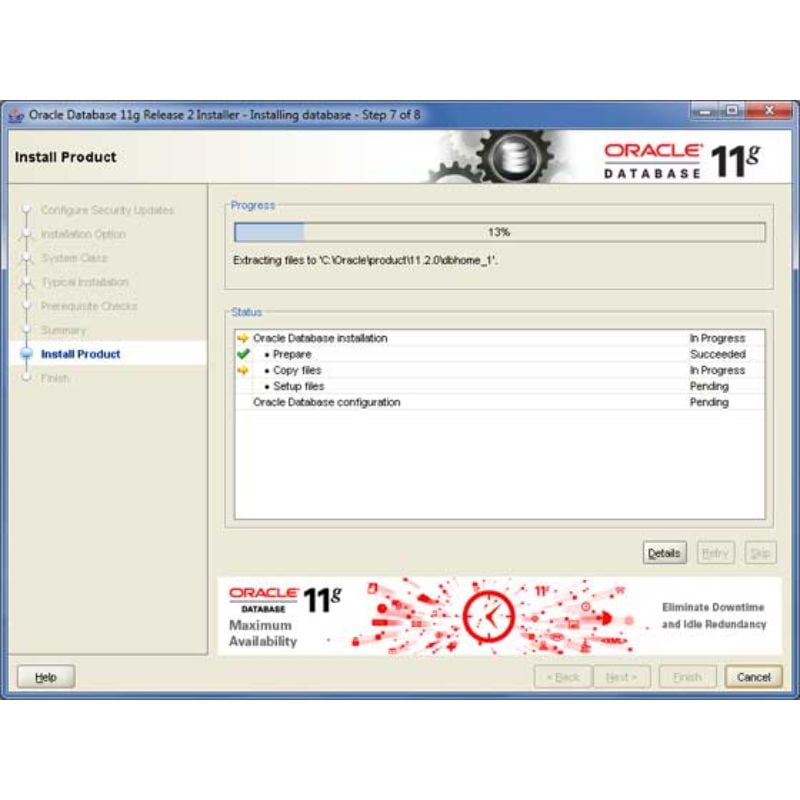

Step 8: Oracle is now carrying out the necessary settings.

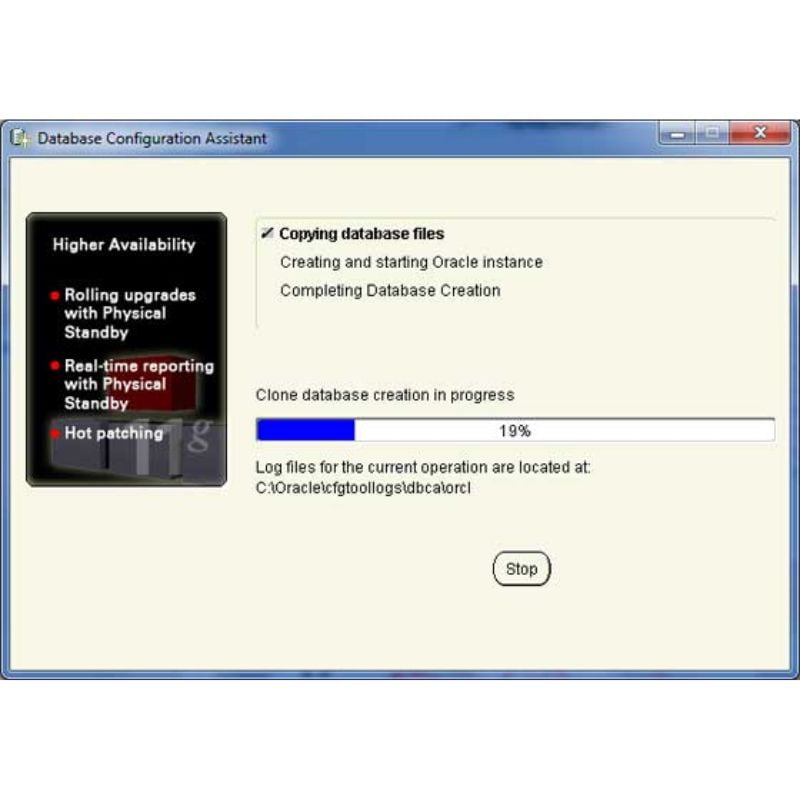

Step 9: The necessary configuration files will be copied here during Oracle installation. It ought to take a moment.

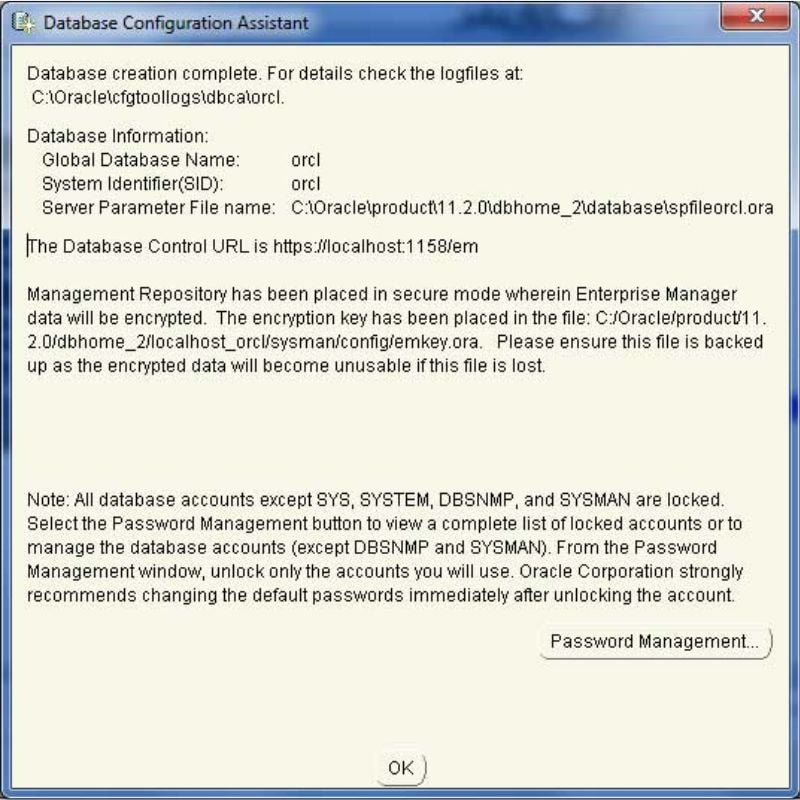

Step 10: After copying the database files, the dialogue box that follows will appear. Simply press the OK button to exit.

Step 11: Now it is the final window.

It’s time to check the installation now. If you are using Windows, type the following command at the command prompt:

sqlplus “/ as sysdba”

The SQL prompt where you will type your PL/SQL scripts and commands should be visible to you.

PL/SQL Data Types

The data types are separated into four categories in PL/SQL:

- Number

- Boolean

- Character

- Datetime

Numeric Data Types

The PL/SQL pre-defined numeric data types and their subtypes are listed in the following table.

| Data Type | Description | Range |

| PLS_Integer | Signed Integer | -2,147,483,648 to 2,147,483,647 / 32 bits. |

| BINARY_Integer | Signed Integer | -2,147,483,648 through 2,147,483,647 / 32 bits. |

| BINARY_Float | Single-precision | IEEE 754-format floating-point number |

| BINARY_Double | Double-precision | IEEE 754-format floating-point number |

| NUMBER(prec, scale) | ANSI-specific fixed-point type | maximum precision of 38 decimal digits |

| DECIMAL(prec, scale) | IBM-specific fixed-point type | maximum precision of 38 decimal digits |

| NUMERIC(pre, scale) | Floating type | maximum precision of 38 decimal digits |

| DOUBLE PRECISION | ANSI-specific floating-point type | maximum precision of 126 binary digits |

| FLOAT | ANSI and IBM-specific floating-point type | maximum precision of 126 binary digits |

| INT | ANSI-specific integer type | maximum precision of 38 decimal digits |

| INTEGER | ANSI and IBM-specific integer types. | maximum precision of 38 decimal digits |

| SMALLINT | ANSI and IBM-specific integer types. | maximum precision of 38 decimal digits |

| REAL | Floating-point type | maximum precision of 63 binary digits. |

Sample Declaration of PL/SQL Numeric Data Type:

DECLARE

num1 INTEGER;

num2 REAL;

num3 DOUBLE PRECISION;

BEGIN

null;

END;

/

PL/SQL Character Data Type

The details of the pre-defined character data types in PL/SQL and their subtypes are as follows:

| Data Type | Description | Range |

| CHAR | Fixed-length character string | maximum size of 32,767 bytes |

| VARCHAR2 | Variable-length character string | maximum size of 32,767 bytes |

| RAW | Variable-length binary or byte string | maximum size of 32,767 bytes |

| NCHAR | Fixed-length national character string | maximum size of 32,767 bytes |

| NVARCHAR2 | Variable-length national character string | maximum size of 32,767 bytes |

| LONG | Variable-length character string | maximum size of 32,760 bytes |

| LONG RAW | Variable-length binary or byte string | maximum size of 32,760 bytes |

| ROWID | Physical row identifier | the address of a row in an ordinary table |

| UROWID | Universal row identifier | physical, logical, or foreign row identifier |

PL/SQL Boolean Data Types

Logical values needed for logical operations are stored in the BOOLEAN data type. The boolean values TRUE and FALSE, as well as the value NULL, are the logical values.

SQL lacks a data type that is comparable to BOOLEAN.

Boolean values can thus not be utilized in:

- SQL statements

- Built-in SQL functions (such as TO_CHAR)

- SQL statements that call PL/SQL routines.

PL/SQL DATETIME Data Types

The century, year, month, day, hour, minute, and second are all included in each date. The valid values for each field are displayed in the following table:

| Field Name | Date Time Values | Interval Values |

| YEAR | -4712 to 9999 | Any nonzero integer |

| MONTH | 01 to 12 | 0 to 11 |

| DAY | 01 to 31 | Any nonzero integer |

| HOUR | 00 to 23 | 0 to 23 |

| MINUTE | 00 to 59 | 0 to 59 |

Variable Declaration in PL/SQL

PL/SQL allocates memory for a variable’s value at the time of declaration, and the variable name designates the storage location.

Syntax

variable_name [CONSTANT] datatype [NOT NULL] [:= | DEFAULT initial_value]

Example

sales number(10, 2);

pi CONSTANT double precision := 3.1415;

name varchar2(25);

address varchar2(100);

Initializing Variables in PL/SQL

One of the following methods can be used during the declaration to initialize a variable with a value other than NULL:

- The DEFAULT Keyword

- The Assignment Operator

Example

DECLARE

a integer := 10;

b integer := 20;

c integer;

f real;

BEGIN

c := a + b;

dbms_output.put_line(‘Value of c: ‘ || c);

f := 70.0/3.0;

dbms_output.put_line(‘Value of f: ‘ || f);

END;

/

Output

Value of c: 30

Value of f: 23.333333333333333333

PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

Variable Scope in PL/SQL

Block nesting is possible in PL/SQL, meaning that a program block can have another inner block inside of it. Two varieties of flexible scope exist:

Local variables: They are those that are declared within a block and are not available to blocks outside of it.

Global Variables: Variables declared in a package’s outermost block are referred to as global variables.

Example

DECLARE

— Global variables

num1 number := 95;

num2 number := 85;

BEGIN

dbms_output.put_line(‘Outer Variable num1: ‘ || num1);

dbms_output.put_line(‘Outer Variable num2: ‘ || num2);

DECLARE

— Local variables

num1 number := 195;

num2 number := 185;

BEGIN

dbms_output.put_line(‘Inner Variable num1: ‘ || num1);

dbms_output.put_line(‘Inner Variable num2: ‘ || num2);

END;

END;

/

Output

Outer Variable num1: 95

Outer Variable num2: 85

Inner Variable num1: 195

Inner Variable num2: 185

PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

Constants and Literals in PL/SQL

A declaration of a constant allocates storage for it and provides information about its name, data type, and value. The declaration may additionally apply the NOT NULL restriction.

Declaring a Constant

The CONSTANT keyword is used to declare a constant. It demands a starting value and prevents modifications to that value.

Example

PI CONSTANT NUMBER := 3.141592654;

DECLARE

— constant declaration

pi constant number := 3.141592654;

— other declarations

radius number(5,2);

dia number(5,2);

circumference number(7, 2);

area number (10, 2);

BEGIN

— processing

radius := 9.5;

dia := radius * 2;

circumference := 2.0 * pi * radius;

area := pi * radius * radius;

— output

dbms_output.put_line(‘Radius: ‘ || radius);

dbms_output.put_line(‘Diameter: ‘ || dia);

dbms_output.put_line(‘Circumference: ‘ || circumference);

dbms_output.put_line(‘Area: ‘ || area);

END;

/

Output

Radius: 9.5

Diameter: 19

Circumference: 59.69

Area: 283.53

PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

PL/SQL Literals

A literal is a clear character, number, word, or Boolean value that isn’t designated with an identifier. The following types of literals are supported in PL/SQL:

- Numeric Literals

- Character Literals

- String Literals

- BOOLEAN Literals

- Date and Time Literals

| Literal Type | Example |

| Numeric Literals | 050 78 -14 0 +327676.6667 0.0 -12.0 3.14159 +7800.006E5 1.0E-8 3.14159e0 -1E38 -9.5e-3 |

| Character Literals | ‘A’ ‘%’ ‘9’ ‘ ‘ ‘z’ ‘(‘ |

| String Literals | ‘Hello, world!’ ‘SLA Courses’ ’29-JUN-24′. |

| BOOLEAN Literals | TRUE, FALSE, and NULL. |

Example

DECLARE

message varchar2(30):= ‘We offer IT Courses for All!’;

BEGIN

dbms_output.put_line(message);

END;

/

Output

‘We offer IT Courses for All!

PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

PL/SQL Operators

The PL/SQL language offers an abundance of pre-built operators, including the following categories:

- Arithmetic operators

- Relational operators

- Comparison operators

- Logical operators

- String operators

Arithmetic Operators

The table that follows lists every arithmetic operator that PL/SQL supports. Assuming that variable A contains 10 and variable B contains 5,

| Operator | Description | Example |

| + | Adds two operands | A + B will give 15 |

| – | Subtracts the second operand from the first | A – B will give 5 |

| * | Multiplies both operands | A * B will give 50 |

| / | Divide the numerator by de-numerator. | A / B will give 2 |

| ** | The exponentiation operator raises one operand to the power of another | A ** B will give 100000 |

Relational Operators

Relational operators return a boolean result after comparing two expressions or values. The table that follows lists every relational operator that PL/SQL supports.

| Operator | Description | Example |

| = | It determines whether the values of two operands are equal; if they are, the condition is satisfied. | (A = B) is not true. |

| !=<>~= | It determines whether or not the values of two operands are equal; if they are not, the condition is met. | (A != B) is true. |

| > | It determines whether the left operand’s value is greater than the right operand’s; if so, the condition is satisfied. | (A > B) is not true. |

| < | It determines whether the left operand’s value is less than the right operand’s; if so, the condition is satisfied. | (A < B) is true. |

| >= | It determines whether the left operand’s value is larger than or equal to the right operand’s value; if so, the condition is satisfied. | (A >= B) is not true. |

| <= | It determines whether the left operand’s value is less than or equal to the right operand’s value; if so, the condition is satisfied. | (A <= B) is true |

Comparison Operators

When comparing one expression to another, comparison operators are employed. Either TRUE, FALSE, or NULL is the outcome in every case.

| Operator | Description |

| LIKE | The LIKE operator determines if it matches the pattern or not and returns FALSE otherwise. |

| BETWEEN | The BETWEEN operator determines if a given value falls inside a given range. |

| IN | The operator IN verifies the membership set. |

| IS NULL | Is EmptyWhen the operand is not NULL, the IS NULL operator returns FALSE; otherwise, it yields the BOOLEAN value TRUE. |

Logical Operators

The logical operators that PL/SQL supports are listed in the following table. Each of these operators produces a boolean result and operates on boolean operands.

| Operator | Description | Example |

| and | The AND operator in logic. The condition becomes true if both operands are true. | (A and B) are false. |

| or | The operator for logical OR. The condition becomes true if either of the two operands is true. | (A or B) is true. |

| not | The sensible NOT operator is utilized to flip its operand’s logical state. The logical NOT operator will render a condition untrue if it is true. | not (A and B) is true. |

String Functions and String Operators in PL/SQL

The concatenation operator (||) in PL/SQL can be used to join two strings together. The PL/SQL string functions are given below.

- ASCII(x): ASCII values for x.

- CHR(x): Character with the ASCII for x

- CONCAT(x, y): Concatenate the strings of x and y.

- INITCAP(x): Converter the initial letter of x.

- INSTR(x, find_string [, start] [, occurrence]); – It returns the location of the find_string when it is found in x.

- INSTRB(x); It returns the value in bytes but the location of a string within another string.

- LENGTH(x); – It gives back how many characters there are in x.

- LENGTHB(x); – It gives the character string length in bytes for a character set with a single byte.

- LOWER(x); – It returns the string after changing the letters in x to lowercase.

- LPAD(x, width [, pad_string]); – Pads x with spaces to the left such that the string’s overall length reaches the width characters.

- LTRIM(x [, trim_string]); – If x matches the NaN special value (which is not a number), the value is returned; if not, x is returned.

- NLS_INITCAP(x); – Similar to the INITCAP function, with the exception that NLSSORT specifies a different sort technique that can be used.

- NLS_LOWER(x); – Similar to the LOWER function, with the exception that NLSSORT specifies an alternate sort algorithm.

- NLS_UPPER(x); – Similar to the UPPER function, with the exception that NLSSORT specifies a different sort method that can be used.

- NLSSORT(x); – It modifies the character sorting process. Before using any NLS function, it must be supplied; otherwise, the default sort will be applied.

- NVL(x, value); – If x is null, returns value; if not, returns x.

- NVL2(x, value1, value2); – If x is not null, return value1; if x is null, return value2.

- REPLACE(x, search_string, replace_string); – Substitutes the value of search_string with replace_string after searching x for it.

- RPAD(x, width [, pad_string]); – To the right, pads x.

- RTRIM(x [, trim_string]); – It gives back a string with x’s phonetic representation.

- SOUNDEX(x); – It gives back a string with x’s phonetic representation.

- SUBSTR(x, start [, length]); – It returns a substring of x that starts at the start point. It is possible to provide an optional length for the substring.

- SUBSTRB(x); – Similar to SUBSTR, with the exception that for single-byte character systems, the parameters are represented in bytes rather than characters.

- TRIM([trim_char FROM) x); – The characters on the left and right of x are chopped off.

- UPPER(x); – it returns the string after changing the letters in x to uppercase.

Example

DECLARE

greetings varchar2(11) := ‘hello world’;

BEGIN

dbms_output.put_line(UPPER(greetings));

dbms_output.put_line(LOWER(greetings));

dbms_output.put_line(INITCAP(greetings));

/* retrieve the first character in the string */

dbms_output.put_line ( SUBSTR (greetings, 1, 1));

/* retrieve the last character in the string */

dbms_output.put_line ( SUBSTR (greetings, -1, 1));

/* retrieve five characters,

starting from the seventh position. */

dbms_output.put_line ( SUBSTR (greetings, 7, 5));

/* retrieve the remainder of the string,

starting from the second position. */

dbms_output.put_line ( SUBSTR (greetings, 2));

/* find the location of the first “e” */

dbms_output.put_line ( INSTR (greetings, ‘e’));

END;

/

Output

HELLO WORLD

hello world

Hello World

h

d

World

ello World

2

PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

Conclusion

We hope this PL/SQL tutorial gives you a basic understanding of Oracle PL/SQL. Gain expertise with our PL/SQL training in Chennai to begin a career in database management.